A story about dnsmasq that wouldn't answer to TCP traffic from k8s pods

So the other day a I was asked to help solve DNS-related problem: one of the Internet domains didn’t resolve from within specific Kubernetes deployment. It turned out to be a rabbit hole that eventually led me to reading source code of coredns and dnsmasq in order to understand what the heck is happening. All with the UDP/TCP and DNS extensions in the background. But let’s start from the beginning.

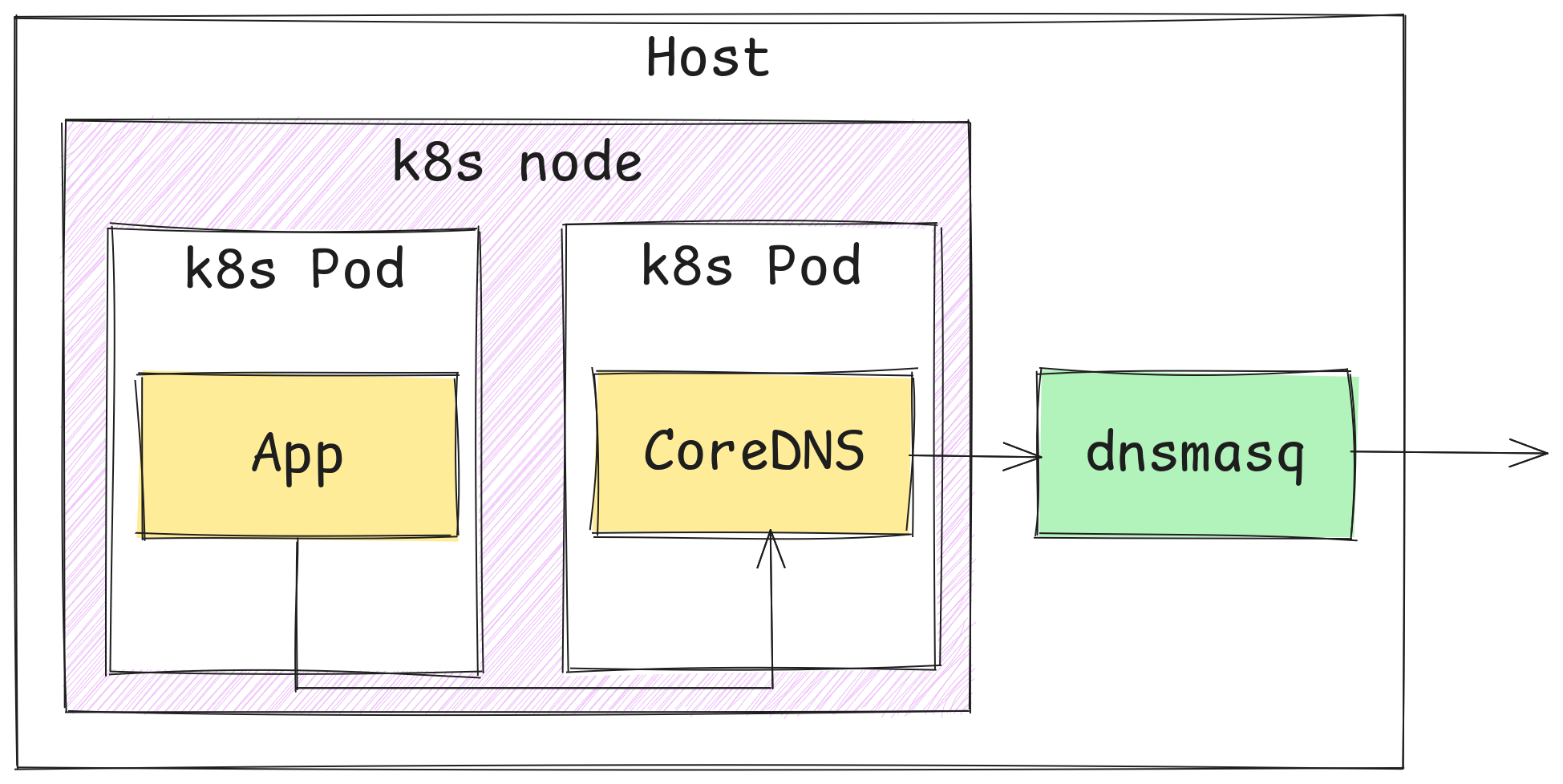

Imagine you have following setup and everything works well for quite a long time, but then it breaks all of a sudden.

Application fails with an exception that reads:

java.net.UnknownHostException: [redacted].azure.com

And it’s a consistent bug (reproductible and repeatable) for that specific domain name, which in the area of troubleshooting is actually a blessing. Nobody likes bugs that don’t reproduce whilst intensive debugging, but randomly re-surface in production clusters.

Let’s dive in!

Checking logs

The application itself is running in a Kubernetes cluster. Name resolution is traditionally handled by CoreDNS deployment in kube-system namespace, so we naturally head there for answers. Though, experienced people already know, that CoreDNS is pretty conservative when it comes to logging, at least when using default configuration. No wonder - names are continuously resolved like hell, logging every request would pile up a lot of log messages quickly.

However, CoreDNS has come up with solution to the problem of not logging every request but still showing erroneous requests: error plugin that seems to work somewhat similarly to rate limiting with leaky buckets. Its messages look like following.

2025-11-26T15:39:36.489892879Z [ERROR] plugin/errors: 2 [redacted].azure.com. A: EOF

2025-11-26T15:39:41.508473593Z [ERROR] plugin/errors: 2 [redacted].azure.com. AAAA: EOF

There it is - a failure for IPv4 and IPv6 respectively. But what’s the meaning of EOF here? Since it can be reproduced in test environment and enabling the logs is so easy in CoreDNS, it would be a sin not to do this. That way more information is revealed.

[INFO] 10.200.xxx.xxx:54776 - 6119 "A IN [redacted].azure.com. tcp 76 false 65535" - - 0 5.00347566s

What’s important here is that it takes more than 5 seconds and then times out. 5 seconds is not an accident, as per CoreDNS sources:

func (f *Forward) ServeDNS(ctx context.Context, w dns.ResponseWriter, r *dns.Msg) (int, error) {

[...]

deadline := time.Now().Add(defaultTimeout)

[...]

}

[...]

var defaultTimeout = 5 * time.Second

CoreDNS evidently times out waiting for upstream server. Or is it? Let’s consult dnsmasq logs before drawing final conclusion. We need to enable verbose logs with log-queries in the config.

dnsmasq: forwarded [redacted].azure.com to 10.x.y.z

[...]

dnsmasq: reply [redacted].azure.com is 51.x.y.z

dnsmasq: query[NS] . from 10.x.y.z

dnsmasq: reply . is <NS>

dnsmasq: reply . is <NS>

[...]

dnsmasq: query[NS] . from 10.x.y.z

dnsmasq: reply . is <NS>

dnsmasq: reply . is <NS>

[...]

So the dnsmasq asks DNS server upstream to itself, receives a reply and should forward it back to CoreDNS. And we can see that process in the logs, but interestingly it is followed by massive amount of unexpected DNS queries: root name (literal dot), record type NS (name server). Moreover, logs indicate that CoreDNS got the reply to original query. Timestamps aren’t visible in the excerpt, but trust me - latency between query and reply was fraction of second.

Suspect for issuing these out-of-place queries is obviously CoreDNS. This behavior is actually documented in forward plugin README file:

When it detects an error a health check is performed. This checks runs in a loop, performing each check at a 0.5s interval for as long as the upstream reports unhealthy. Once healthy we stop health checking (until the next error). The health checks use a recursive DNS query (

. IN NS) to get upstream health.

That explains dnsmasq logs. But it raises question: why CoreDNS marked our dnsmasq server as unhealthy?

At that point I already knew where it was going, so I pulled dnsmasq source code directly from its git repo, compiled it on target machine and ran it in foreground.

sudo ./src/dnsmasq -d --log-debug 2>&1 | tee /tmp/dnsmasq.log

The --log-debug option was not available in the dnsmasq shipped with the OS, and it was pretty crucial as it turned out. It made following line appear in dnsmasq logs right before the health checks start.

dnsmasq: reply is truncated

DNS, in default settings, works over UDP, which suffers from max packet size. But wait - it can’t be that if some name has lot of records then it becomes “unresolvable”. After all, DNS is backbone of the Internet, such a restriction would be very limiting.

Digging in (literally)

In the meantime I gathered packets from the wire using tcpdump and then had a look. That eventually enabled me to get rid of Uber-jar I was using to reproduce the problem and instead use dig. Much less cumbersome, but reproduction wasn’t straightforward. I tried following, unfortunately to no avail. It was always succeeding.

dig [redacted].azure.com A

I sniffed some more packets to eventually discover that dig by default uses EDNS0, whereas my Uber-jar was not using it. Touché.

What is this EDNS0?

Quick search points to “RFC 9715 IP Fragmentation Avoidance in DNS over UDP”, which begins with:

The widely deployed Extension Mechanisms for DNS (EDNS(0)) feature in the DNS enables a DNS receiver to indicate its received UDP message size capacity, which supports the sending of large UDP responses by a DNS server. Large DNS/UDP messages are more likely to be fragmented, and IP fragmentation has exposed weaknesses in application protocols.

The puzzles start to match. The original client doesn’t use EDNS the way dig uses it, the reply from the upstream (upstream to dnsmasq) server is already truncated, and the dnsmasq has no option but to empty it. Otherwise it could end up even worse.

Equipped with this knowledge let’s do:

dig [redacted].azure.com A +noedns

And we get:

;; Truncated, retrying in TCP mode.

[...]

;; ->>HEADER<<- opcode: QUERY, status: SERVFAIL, id: 28742

[...]

;; Query time: 5009 msec

This single line is super interesting: dig decided to switch to tcp, because it was informed that the reply is truncated. So-called TC bit is set in the reply, as per RFC 1035:

Messages carried by UDP are restricted to 512 bytes (not counting the IP or UDP headers). Longer messages are truncated and the TC bit is set in the header.

But after switching to TCP it breaks and triggers the recursive NS . query. Why? Before we get to that, we can check what happens when we instruct dig to use TCP straight away:

dig [redacted].azure.com A +tcp

It has the same effect, so from now on let’s use short-circuited incantation that triggers the problem.

Looking again at sniffed TCP packets I observed unexpected TCP RST:

It looks like dnsmasq is not happy with something and it closes the TCP connection almost instantaneously after it has been made. I was afraid that it crashes, but it doesn’t. This is the moment when manual compilation of dnsmasq pays off, because we can augment it easily with extra debug logs.

But accidentally, before doing so, I checked what happens if I run dig from the host machine against dnsmasq (in other words not from within a Kubernetes Pod). To my surprise it worked!

I immediately thought that maybe docker is the layer that introduces some problem, but it was another surprise to see that it works well from within manually started container. But that was already something, because it became clear that only from Kubernetes Pod the TCP DNS resolution fails.

I also did quick experiment: I ran CoreDNS locally on my machine and connected it both to remote Kubernetes cluster (API server) and remote dnsmasq. The configuration was almost the same, the only differing bit was path to kubeconfig file. And it worked too.

Looking at network packets I saw clearly that dnsmasq, for some unknown reason was very picky about who was making TCP request. And if it originated from Kubernetes Pod, it was retroactively rejected.

Looking under the bonnet of dnsmasq

At this point I had to look in the dnsmasq source code.

static void

do_tcp_connection(struct listener *listener, time_t now, int slot)

{

int confd, client_ok = 1;

[...]

while ((confd = accept(listener->tcpfd, NULL, NULL)) == -1 && errno == EINTR);

[...]

enumerate_interfaces(0);

if (option_bool(OPT_NOWILD))

iface = listener->iface;

else {

[...]

for (iface = daemon->interfaces; iface; iface = iface->next)

if (iface->index == if_index &&

iface->addr.sa.sa_family == tcp_addr.sa.sa_family)

break;

if (!iface && !loopback_exception(listener->tcpfd, tcp_addr.sa.sa_family, &addr, intr_name))

client_ok = 0;

}

[...]

}

Well well well. It looks like dnsmasq accepts the connection first (with call to accept), but then checks from which interface it came, and if it came from wrong interface, it closes incoming connection.

if (!client_ok)

goto closeconandreturn;

[...]

closeconandreturn:

shutdown(confd, SHUT_RDWR);

When our packet arrives from outside, it goes through equivalent of eth0. When it comes from docker, it goes through docker0. And dnsmasq is happy about that. Kubernetes networking can be handled by any CNI plugin. We’re using Calico and it seems that Calico does something that dnsmasq doesn’t like.

But what? And also: why dnsmasq accepts TCP connections just to drop them several lines later?

Additional debug prints showed me that actually not the interface is the culprit, but what kind of addresses are assigned to such interface. Following condition in the code is the one that fails:

if (iface->index == if_index &&

iface->addr.sa.sa_family == tcp_addr.sa.sa_family)

The right interface is found, but the socket families differ: Calico iface is AF_INET6 (IPv6), whereas incoming connection is AF_INET (IPv4).

And this is our root cause: dnsmasq expects both packet and interface it came from (as reported by OS) to share the same socket family. If they do not, dnsmasq rejects the connection.

How dnsmasq binds to network interfaces?

Naturally one has question: why dnsmasq rejects connections retroactively? Under Linux it is possible to attach socket to any interface in the system. This is helpful for long-running services to handle traffic even if network interfaces come and go, or change their addresses.

dnsmasq has two functions to setup this: create_wildcard_listeners or create_bound_listeners. When bound listeners are created, routing is handled entirely by the OS, so the problem with rejected connections doesn’t happen. It was pointed out to me in dnsmas-discuss mailing list that Linux uses weak host model, and it’s the reason why it works.

Why Calico interfaces are recognized as IPv6 ones?

In order to understand this we need to scratch a little bit of how networking in Kubernetes works. By no means I’m network engineer, so I won’t pretend I understand every aspect, but in a nutshell: each Pod will receive it’s own network interface named cali<some hash>. There will be virtual ethernet pair created for it that connects that virtual network interface with host network interface, like an ethernet cable.

For instance, imagine we have a Pod with IPv4 address 10.200.x.y. Using following command we get which network interface it belongs to.

$ ip route get 10.200.x.y

10.200.x.y dev cali494e9eda238 src 10.x.y.z uid 1000

Now, let’s see the interface:

$ ip a show cali494e9eda238

178: cali494e9eda238@if2: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1450 qdisc noqueue state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether ee:ee:ee:ee:ee:ee brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 3

inet6 fe80::ecee:eeff:feee:eeee/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

And inside the Pod:

$ ip a show eth0

2: eth0@if178: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1450 qdisc noqueue state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether [redacted] brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff link-netnsid 0

inet 10.200.x.y/32 scope global eth0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fe80::6c43:21ff:fe07:80bf/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

Notice how the interface on the host level has only inet6 address, whereas on the Pod side it has both inet and inet6. Most importantly, dnsmasq upon interface enumeration, will recognize Calico interfaces as inet6 one and remember it. The code responsible for that is located in netlink.c, function iface_enumerate, which is so obscure that I will abstain from including it here.

Conclusion

DNS and networking in Linux is simple. Just read fine printcode.